Indistylemen

The Anatomy of a Suit Jacket: A Comprehensive Vocabulary

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Suits come in two basic flavors–single and double breasted–but, beyond that, a suit jacket is one of the most complex tailored items out there, made up of numerous component parts that we may not think about that much. However, each aspect of a suit’s design adds something to how it looks on you. In this article, we’ll review the anatomy of a suit, with an emphasis on the important terminology used to describe its various features.

What is a “Suit”?

Though it may seem obvious, it may be worth mentioning first of all that a suit is comprised of a jacket and pants in matching fabric that forms a set, hence its name in French: complet. As Sven Raphael Schneider has explained elsewhere, the modern English word comes from the French suivre, “to follow,” with the pants following the jacket (or vice versa). When I’ve worn a sport coat and non-matching trousers, I’ve received compliments on my “suit,” which is technically incorrect, though as a gentleman, I accept the compliment without correction. One thing this error does reveal is the primacy of the suit jacket–the pants are mostly an afterthought–and we too will focus our attention on the jacket where most of a suit’s defining features are concentrated.

Sven Raphael Schneider in a Navy Double-Breasted Suit

When I first started buying suits as a younger man, I thought they were all essentially the same, and in my mind, I was picturing the typical cut of a suit sold in Macy’s—loose fitting yet quite structured, with padded shoulders and a boxy cut. This never really sat well on my body, so I ended up avoiding suits altogether–until I learned to see all the individual elements that go into their design. Just like many working mechanical parts and design features come together to make a Ferrari look and run like a Ferrari and a Toyota look and run like a Toyota, not all suits are alike. I was amazed to see how a change to just one element of a suit’s design can affect its overall look and style.

Lapels

A suit’s lapels are a major factor in shaping the impression of a suit, as they are a prominent design feature right in the center and close to eye level. Lapels can be defined as flaps of fabric on each side of the suit jacket immediately below the collar and folded back. This “folding back” is best captured in the French name revers, also used in Italian, which emphasizes a turning back of the fabric direction.

Notch lapel

Gianni Agnelli projecting authority in a peak lapel suit.

Gorge height often meets your shoulder line.

Another way to think about this is that the gorge should rest on your collarbone. Still, gorge height can vary. Suits from the early to mid 20th century tend to have a lower gorge, and it has begun to migrate upwards in recent years toward the top of the shoulder, so it is sometimes barely visible from the front. The latter appear especially in Italian tailoring, including Sartoria Rossi and Cesare Attolini. A low gorge can be seen as either dated or classic depending on your perspective while a high gorge can be considered either rakish because it creates the impression of a broader chest and greater height, or a mere whim of fashion.

A contemporary Attolini suit with a high gorge; Gary Cooper in the late 1930s wearing a suit with a low gorge

A J.CREW Ludlow suit with skinny lapels compared to an Orazio Luciano suit with wide lapels.

A Pini Parma jacket showing the curve of a lapel belly. Notice how the large lapels reduce emphasis on the shoulders.

Hollow formed under the lapel roll

Suit Buttons

A low buttoning point on Benedict Cumberbatch’s one-button jacket compared to a higher one on Sven Raphael Schneider’s three-button jacket.

The author, Dr. Lee, in a three-roll-two glen check with contrast-stitched button gimp.

Various double-breasted jackets, also possible as suits: a classic 6×2, a 4×2 and what looks like an 8×2.

Three kissing buttons on a summer jacket

Finally, we include the lapel buttonhole here, as it originally was designed as a way to fasten your collar under your neck as a remedy against bad weather, that is, until the button on the opposite side disappeared from the design. Now, this function is vestigial, but the hole has become the perfect place for a boutonniere flower for a dash of added style. Hand-sewing of the buttonholes, including the one on the lapel, is often a hallmark of a bespoke or otherwise high-quality suit. The most popular is called the Milanese buttonhole because of its origins among tailors of that city; this involves fine stitching of the gimp–the reinforcing trim threads of the buttonhole–resulting in an added bit of ornamentation.

Milanese buttonhole on a lapel.

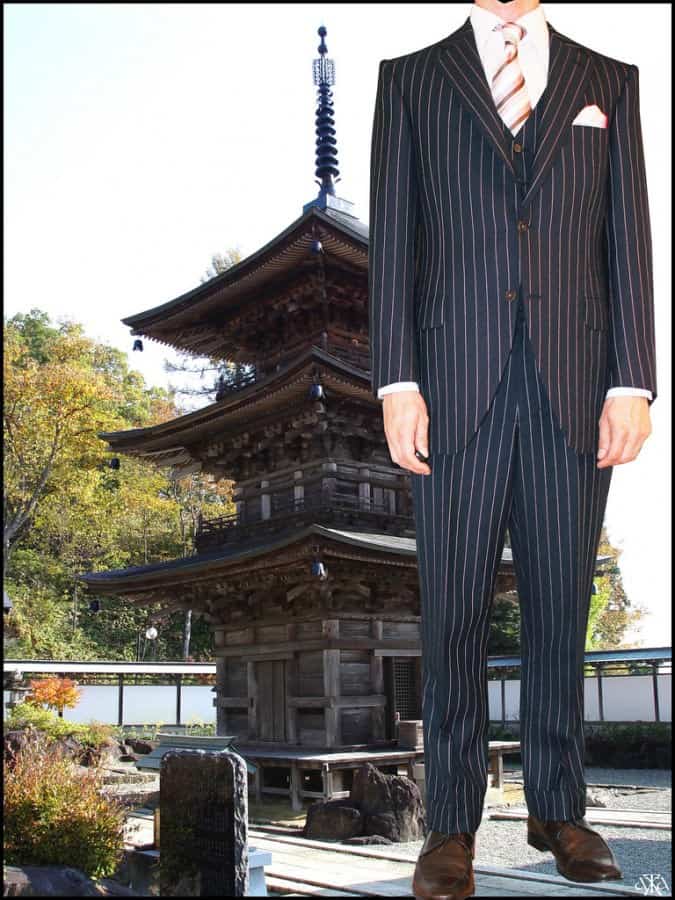

Shoulder Terminology

Much can be done by a tailor with a suit’s shoulders to influence its final appearance. British tailoring traditionally favors a structured shoulder with padding that creates a stronger, masculine look: imagine a pinstripe suit worn by a banker. You will also see this in French power suits and Italian tailoring from Milan and Florence. It is possible to create the illusion of broader shoulders through constructing an extended shoulder, which projects the fabric of the shoulders out a bit further than the arms through the assiduous use of padding.

Colin Firth in Kingsman wearing a classic British suit with padded shoulders

Another option, with light padding, is the roped shoulder of Neapolitan style, where the sleevehead (top of the sleeve) is attached to the armhole a bit higher than the shoulder, creating a ridge or “roping” detail. In Italian, the name is spalla con rollino (“shoulder with a little roll”). Roping can also be part of a pagoda shoulder, which is slightly concave due to some padding, which results in an elegant sweep down from the collar and back up at the arm, like the roof of a pagoda. In Italian, such a shoulder is actually termed a spalla insellata (saddle), as it curves like a saddle. This creates a very bold and unique look, which is not for everyone!

A suit with pagoda shoulders and roping.

If we go without any padding, we end up with what is termed a soft shoulder or natural shoulder also most typically seen in Neapolitan tailoring. The result is a more relaxed look that Bloomberg has called “risky trend” if you work in a strict business environment but ideal to raise business casual to a new level or for weekend wear. The absence of padding creates a spalla camicia (shirt shoulder), where the arm of the suit jacket lies like a shirt sleeve, which, of course, is also unpadded.

Spalla camicia vs. con rollino shoulder details

All soft Neapolitan shoulders, including those with light padding, can also feature additional shirring of the sleevehead (called a mappina or “little rag”). These are little puckered pleats that show the tailor’s handwork and are evident in most images of spalla camicia suit jackets.

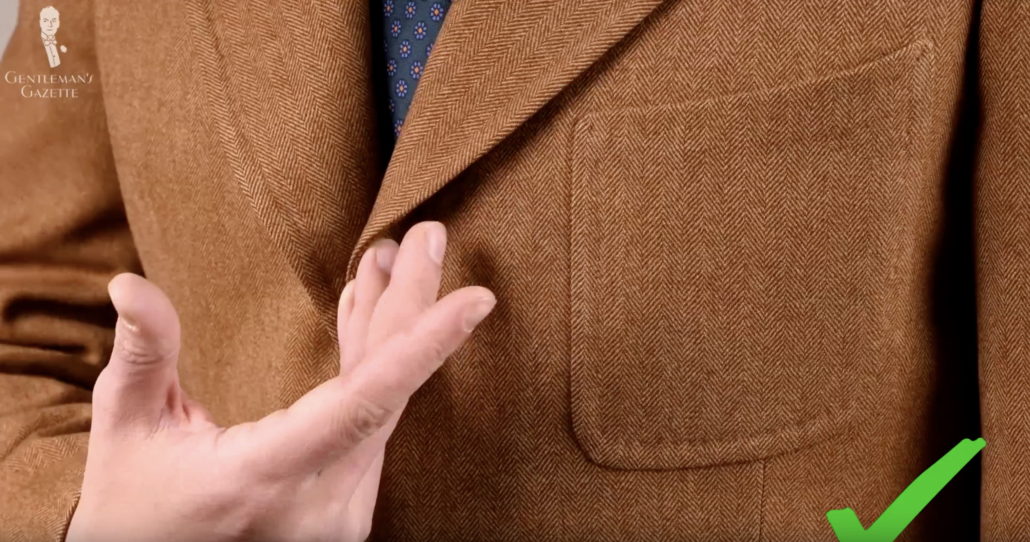

Pockets

Every suit jacket will have at least two kinds of pockets. One, on the upper right side, is the breast pocket, into which you can (and should) place a pocket square. Again, the Neapolitan tailors have done something unique here, creating a breast pocket that is curved like a little boat (barchetta) for a unique hit of style.

Jacket pockets formality scale

In terms of the larger pockets, there are three possibilities, and which one you have plays a key part in determining how casual or formal a suit is. First, we have patch pockets, which are sewn onto the outside of the suit as visible patches; these immediately signal a suit is more casual, perhaps a summer linen. These may also appear as a breast pocket, which is really informal on a suit. Flap pockets are hidden beneath the surface of the suit jacket except for a flap of cloth covering them. These are the most common or default suit pocket type. Third, you might encounter jetted pockets, which are also beneath the surface of the jacket but have no covering flap. These can appear on suits, as they are highly formal, but are more common on dinner jackets. When you buy a new suit, your pockets will be basted or sewn shut. As the stitching is hidden, some men keep the pockets closed to avoid deforming or warping the pockets by putting things in them, especially patch pockets.

On some flap pocket suits, you will also find a third, slightly smaller, ticket pocket on the left side above the regular flap pocket. This was originally designed to hold train tickets but can be used for various small items.

Single Breasted Suit With Ticket Pocket

The Body Panels of a Suit

Given how much is going on related to the shoulders, lapels, buttons and pockets on a suit, it is easy to overlook the body panels themselves, which can also contain variations. A primary consideration is how much fabric there is in the chest area, also known as the drape. A suit jacket with a lot of drape has a fuller cut with more room in the chest. The look differs considerably from the more fitted suits that are in style now but have returned at places like The Armoury and Ring Jacket because suits with drape are seen as more laid back as well as comfortable.

A drape suit from the 20th century and a contemporary Ring Jacket suit with some drape to the chest area. Darts are visible in the right image as well.

Also on the chest, you are likely to have darts–vertical seams running down each side of the panel, usually ending above the side pockets. They’re designed to add some contouring to the shape of the suit jacket and are present in most modern suits unless you have a true American sack suit, which is meant to lie loosely on the torso, like a sack, truly the antithesis of contemporary suiting style.

Waist suppression and darts visible on this suit jacket (and a ticket pocket to boot).

Moving down the jacket, we have the question of waist suppression. As the name suggests, this is how much the waist area of the suit is tapered in, creating the impression of wider shoulders by slimming the waist. Waist suppression is related to drop, which is a number indicating a difference between the size of your suit jacket and the waist size of your suit pants. For example, if you have a 40 jacket size and a 34 waist size, this is a standard “drop 6” suit. If the suit is cut slimmer, you may see it referred to as a “drop 7” or even “drop 8,” the latter being a 40 jacket and a 32 waist. Even though the number includes consideration of the pants size, the jacket itself in a drop 7 or drop 8 suit will be slimmer than one in a drop 6.

At the very bottom of the suit, we have the quarters, the two flaps of the jacket that meet at the waist button. These can be either open or closed, meaning the flaps can lie nearly straight down (closed quarters) or spread apart in a “flyaway” or “cutaway” fashion (open quarters). The effect of open quarters is to make the lower body look wider, so suits with this feature may be ideal to balance out very broad shoulders. On the other hand, closed quarters maintain emphasis on the shoulder because the hip area stays narrow.

Open quarters on a suit.

Taken together, the quarters form part of the suit skirt, which comprises all of its lower half. On the back of the skirt there would usually be one or more vertical slits, known as vents. These likely originated to enable a jacket to sit well when riding on horseback. Nowadays, they serve the same purpose of keeping the back of your suit from rumpling wherever you sit, and, for all intents and purposes, you’d want to choose a double vent rather than a single center vent or none at all. Besides keeping your suit looking neater when you sit, a double vent keeps your rear end covered if you put your hands in your suit pockets. What’s more, a single vent is usually a hallmark of a cheap suit because they are less expensive to make. The only time you should have something other than a double vent is when wearing a dinner jacket or tuxedo, which is usually ventless because this creates a sleek, streamlined silhouette. Of course, you can have the same slimming effect if you buy a ventless suit, but you would have to be willing to sacrifice the advantages of having vents.

Silhouette of double vents on a suit

The Hidden Bones of a Suit

As with human anatomy, some of the anatomy of a suit lies beneath the surface. First, there is the lining, which should be made from cupro, a natural material, rather than polyester. Bemberg is another name you may hear related to lining; it’s just a specific high-quality brand of cupro. The lining adds warmth as well as structure to a suit jacket, helping it hang well on the body, smoothing it out by placing a thin layer between the suit fabric and your shirt. Gents with dandy style may choose linings in colors that contrast that of the suit while adding panache. Since lining does add thickness, summer jackets often contain less lining and are either half lined (top, side panels and sleeves), quarter lined (top and sleeves), or even totally unlined, depending on how much there is on the inside. Usually, regardless of how little overall lining there is, the sleeves of the jacket would remain lined for ease of slipping the jacket on and off.

Contrast Lining Dege Skinner

While you can see the lining of a suit, the canvas is invisible, a layer made of wool and horsehair (for stiffness) that sits between the suit fabric and the lining. The purpose of the canvas is to help the suit hang optimally and conform it more to your form. In fact, you’ll often hear it said that canvas actually improves the look of a suit over time as the heat of your body shapes it to fit. The canvas is stitched loosely in between layers so that it moves with you.

Exposed canvassing on suits

Similar to the lining, you can have a suit that is fully canvassed or half canvassed. The former covers both front panels of the suit and the lapels. A half canvas covers just the upper chest and lapels; it doesn’t extend down to the quarters. The tailoring work involved with canvassing is intensive and costly, so full canvas will be more expensive. Cheaper suits will have only a fused interlining that is glued in between the suit fabric and lining, which has a tendency to warp and bubble over time due to delamination (unsticking of the glue). Thus, it is crucial to invest in a suit that is at least half-canvassed and avoid fusing.

Bubbling of a fused interlining due to delamination.

Conclusion

Once you have knowledge of what makes up a suit and the vocabulary to describe these features, you can choose a suit that suits you—especially in terms of your age and body type. It takes some time to see the elements when you begin the process of wearing tailored clothes, but learning about them is the first step to looking and feeling your best in a suit. It is important to observe that the various choices in the design of a suit not only determine its anatomy but help to enhance yours as well.

from Gentleman's Gazette https://ift.tt/2N3jWzN

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment

thanks for your feedback