Indistylemen

The Steak Guide, Part I: Characteristics & Types of Cuts

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Steak. For many men, it’s their favorite meal, a treat at a restaurant, or a point of pride in their home cooking repertoire. It’s such an important food in many cultures that entire restaurants are dedicated to perfecting it, and the definition of a perfect steak is hotly debated.

Even though it’s a deceptively simple dish, requiring only a bit of seasoning and some heat, there are many things to know about steak before you get started grilling, searing or ordering one. Therefore, this article will discuss what exactly a steak is, the characteristics of a good one, and the best cuts to buy.

What Is Steak?

It may seem like an overly simplistic question, but there is, in fact, a bit of nuance to it. After all, not just any piece of meat is automatically considered a steak. The actual definition, then, is as follows: a cut of meat, usually beef, that’s sliced perpendicular to the muscle fibers. While this definition can apply to other types of meat, this particular series of articles will focus specifically on beef steaks, a staple in western cultures.

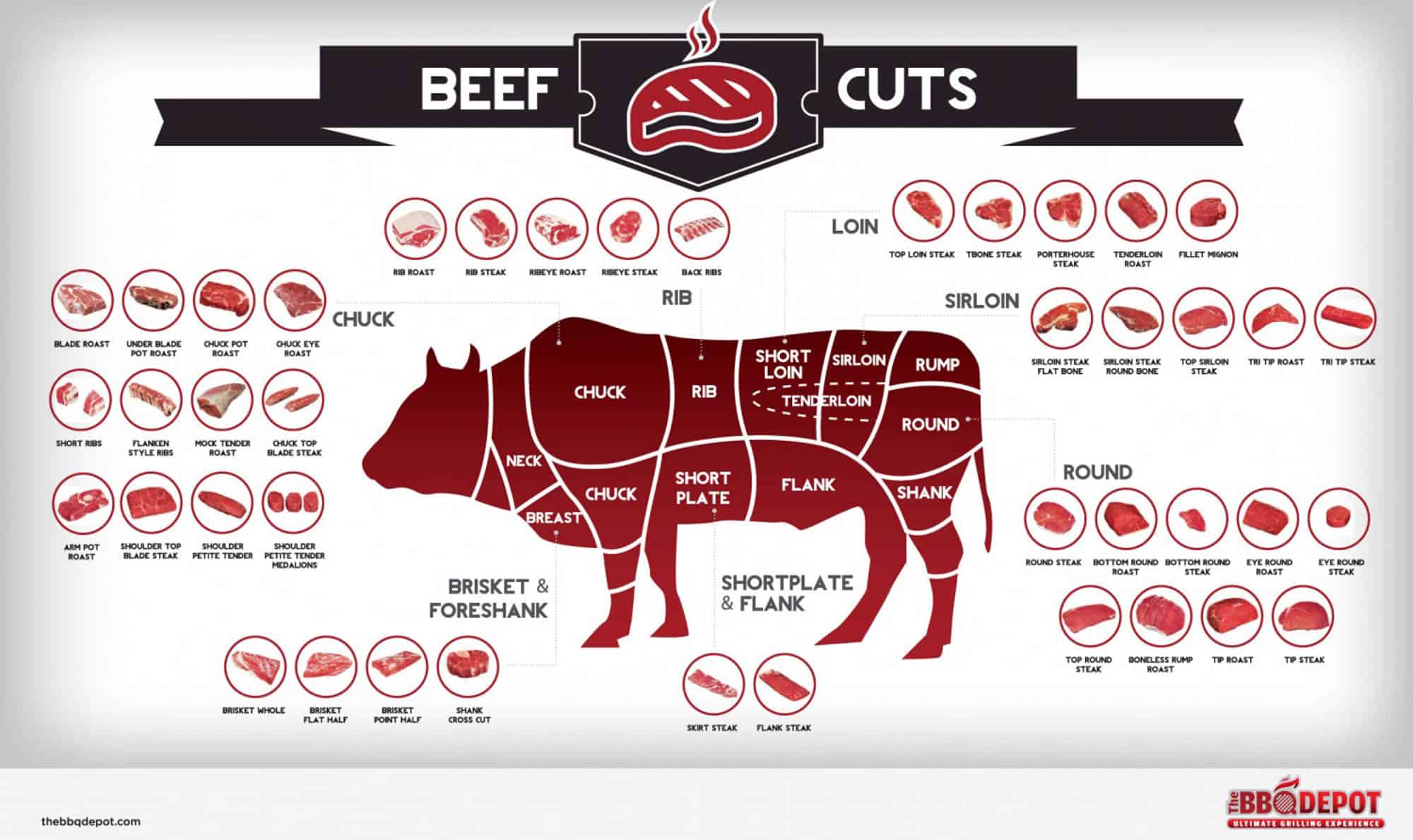

Various cuts of beef, as can be found at a typical butcher shop.

Steak Controversies

Before we go any further with specific information, there are a few important considerations that we feel obligated to address.

- In short: while steak is delicious, beef is controversial.

- It’s an expensive, resource-intense food that is damaging to the environment.

- Cattle are not always raised under humane conditions, and antibiotic use in animals has been linked to growing antibiotic resistance.

- Furthermore, beef is definitely not a health food. In fact, the World Health Organization links regular consumption of red meat to an increased risk of cancer.

While many attempts have been made to reframe red meat as healthy (such as the “paleo diet” or advocacy of eating grass-fed beef) it simply isn’t. Ultimately, everyone must choose for themselves if or how they consume red meat.

Cattle on a ranch near Elko, Nevada, USA.

Characteristics of a Great Steak

Now that we’ve covered our necessary disclaimers, let’s get back to discussing the particulars of what makes for a good steak. Overall, there are two key characteristics of a steak to consider: tenderness and flavor.

What Makes a Steak Tender?

The importance of tenderness can’t be underestimated; “tenderizing” a steak is a popular search topic for that reason. Tender cuts are easy and enjoyable to chew. Nobody’s idea of a good steak should include a dining experience that resembles chewing on a piece of leather! With that in mind, the simplest way to achieve a tender steak is to start with a tender cut of beef. When considering tenderness, let’s look at the characteristics of the steak itself and set aside the cooking method for later consideration (which is to say, the second article in this series). There are two key considerations when it comes to tenderness:

-

How much the muscle was used

Just as humans exercise different muscles to different degrees, the same is true for cattle. The less a given muscle was used by the cow in question, the more tender that the resulting cut of meat will be. For example, the muscles along the backbone (which are cut into many of the steak types we’ll discuss below) are used much less than the hips and shoulders (which end up as cheaper cuts, like chuck).

-

The ratios of muscle, collagen, and fat in the steak

A steak contains three main types of bodily matter, not counting a bone: muscle, collagen (a type of connective tissue which holds muscle together), and fat. Muscle is the primary substance of the steak, fat provides flavor, and collagen provides structure. During cooking, connective tissues do not have enough time to break down; therefore, tender cuts of steak should contain less connective tissue overall. Finely marbled fat will melt during cooking, but thicker pockets of fat will not; this compromises tenderness.

This is why finely but intensely marbled Wagyu or Kobe beef is so prized–but we’ll address these types of beef later in the article.

A chart showing the various grades of beef marbling, using the Japanese BMS (Beef Marble Score) index.

To summarize, the most tender cut will come from around the backbone, has very little connective tissue, and has finely marbled fat. For these reasons, as well as the fact that the more tender muscles are often smaller, you can expect to pay more for a tender cut of beef.

What makes a steak flavorful?

Again, let’s just consider the flavor of the steak itself rather than any seasonings that might be added during or before cooking.

The main components that contribute to flavor are the amount of fat in the meat, the diet of the animal it came from, and how the meat has been aged.

-

Fat is the main flavor component in steak.

- Meat is mostly composed of muscle tissue, and therefore water.

- Flavor-carrying molecules are repelled by water, but they dissolve in fat; therefore, fat enhances flavor.

- As a further such enhancement, fat also adds to the juiciness of the steak.

A cut of beef such as the one pictured here, with little connective tissue and finely marbled fat, will be more tender and flavorful.

-

The animal’s diet also has an impact on flavor.

- Grain-Fed Cows

For the most part, grain-fed cows are left to roam free for their first six to twelve months. After that, however, they’re moved into feedlots, which are no longer pastoral environments, but more concentrated areas. In the feedlots, the cows are rapidly fattened up with grains such as corn or soy. Some cows are even given hormones to help them grow faster and antibiotics to help increase their survivability in the concentrated and sometimes unsanitary living conditions. As you might imagine, these feedlots and the conditions therein are one of the principal complaints when considering the inhumane treatment of beef cattle. - Grass-Fed Cows

Unlike grain-fed cows, grass-fed cattle are often left to graze for the entirety of their lives before going to the slaughterhouse. While the term grass-fed isn’t a legal definition, according to best practices it typically implies that cow will subsist mainly on a diet of grass, hay, or shrubbery. Grass-fed cows typically have less fat in their meat; this is because grass is less nutritionally dense than grain. Grazing cows also move more, which makes their meat a bit tougher. - Grain-fed is often labeled purely as “beef,” whereas grass-fed or grass-finished, which captures the flavors of both feeds, is usually labeled as such.

- Note that the USDA does not regulate the labeling of grass-fed beef, so the discerning shopper may want to inquire further of their butcher or grocer.

- At the end of the day, it is a matter of personal taste, so don’t be too concerned and choose what you like. We believe that if flavor is your aim, traditional grain-fed beef is going to be your best bet, although some people may prefer the flavor of grass-fed beef.

- In general, remember that it always pays to know where your steak comes from, as the characteristics of the cattle will have an impact on the quality of the meat.

- Grain-Fed Cows

-

Finally, how the meat is aged also affects flavor.

- Stated simply, aging is the process by which microbes and enzymes act upon meat to help break down its connective tissue, increasing both tenderness and flavor.

- While one might assume at first that a more freshly butchered cut of beef would be more flavorful, this couldn’t be further from the truth! “Fresh” beef is tough and flavorless, as its connective tissues are all still intact. While some grocery stores sell “non-aged” beef, such material is still aged for at least a few days. Further, this “non-aging” is simply a hallmark of lower-quality cuts whose suboptimal flavor would not benefit from additional aging.

- Dry Aging

- In the traditional dry-aging process, steaks are aged by hanging them for about 30 days; due to the water loss, the beef flavor intensifies. Moreover, microbes on the outer surfaces of the meat are allowed to create a distinctive aroma and textured exterior.

- Today, meat lovers often choose dry-aged beef over wet-aged beef because they like the stronger flavor. Generally, a standard grocer won’t carry dry-aged beef, while a reputable butcher often will. Furthermore, only premium cuts are typically dry-aged, because lower-quality cuts like flat-iron, chuck, or skirt steaks would simply degrade rather than improve – this is chiefly due to said cuts’ lower and less-evenly distributed fat content.

- Dry aging is a delicate and therefore expensive process, as the meat must be stored at near-freezing temperatures in a humid environment (35-38 °F, or 1.5 To 3.5 °C, with a humidity of 50-60%).

- Proper dry aging can take from two to six weeks’ time, and approximately a third or more of the weight is lost as moisture.

A selection of dry-aged cuts of beef. Note the dark and textured exterior.

- Wet Aging

- Most beef is wet aged in this day and age, by way of vacuum-sealing cuts of beef in plastic bags.

- This process not only helps to keep the meat fresh for a longer period of time, but also reduces the loss of water (meaning a higher value for the vendor, as steak is sold by weight).

- Further, said process takes less time than dry aging (usually 4 to 10 days at a minimum) and helps retain the appetizing red color of fresh meat, which is seen as desirable by many consumers.

- Just because we’ve already discussed how the loss of water-weight can lead to more flavor, that doesn’t mean that wet aging is necessarily inferior. Some vendors even start with dry aging and then switch to wet aging to get the best of both worlds.

- Ultimately, our suggestion is to simply try for yourself, and once you have a favorite, take notes so you can get exactly what you like with future visits to the grocer or butcher.

Steak Cuts

There are many types of steak cuts; in simplest terms, a “cut” refers to the part of the cow from which the steak was sourced. The most tender cuts come from the loin and rib around the backbone, and as they typically have the best texture and flavor, these are the cuts on which we’ll be focusing today. We believe the top five cuts for tenderness and flavor are:

-

Ribeye

-

Tenderloin

-

Strip

-

T-Bone & Porterhouse

-

Top Sirloin

While they are all worth eating, a great many people will likely attest that the best combination of flavor and tenderness comes from the first three cuts on this list in particular. Of course, you might also enjoy other cuts (for example, a flank or flat-iron steak), but as we believe that the five cuts listed here represent the best combination of texture and flavor, they’ll remain the focus of our discussion. Now, let’s talk about each one.

Ribeye

- This cut is sourced, perhaps obviously, from the rib section of the cow (remember to check the infographic above!), and is also used, when slow-roasted, for prime rib.

- Also known as a Delmonico steak, Scotch fillet, or entrecôte.

- In the United States, a terminological distinction is made: “ribeye” refers to the cut when the bone has been removed, whereas “rib steak” refers to the cut if the bone remains attached. In other parts of the world, these terms are largely interchangeable.

- We believe that the ribeye represents the best choice for those who prize flavor above all else; for its well-marbled fat and high degree of tenderness, the flavor of a ribeye is second to none.

An example of a ribeye, with a good amount of marbling.

Tenderloin

- This cut, sourced from the center of the loin regions, is aptly named, as it is the most tender cut of meat on a cow.

- Also known as the filet in France, the fillet in the United Kingdom, and the eye fillet in the Australasian region of Oceania.

- The three main “cuts” of the tenderloin are (in order from largest to smallest) the butt, the center-cut, and the tail. The butt end is usually suitable for carpaccio, the center-cut for portion-controlled steaks like the coveted filet mignon and Chateaubriand, and the tail for recipes where small cuts of beef are used, such as Stroganoff.

- Filet mignon (which means “small” or “dainty” in French) is sliced from the small end of the center cut, whereas Chateaubriand (named for the 19th-century French ambassador, François-René de Chateaubriand) comes from the large end.

- The average animal only nets about 3.5 pounds of tenderloin, with about 2.5 pounds suitable for Chateaubriand and one pound for filet mignon. The weight of the tail portion will vary from 0.5 of a pound to almost nothing. As you might imagine, the tenderloin is therefore the most expensive cut by weight.

- As it is leaner than the ribeye or strip, this cut is the better choice for those who prefer texture over flavor; it’s often described as being “melt-in-your-mouth” tender.

- At the same time, because it’s not as flavorful as the ribeye or strip, the tenderloin is often wrapped in bacon or served with a sauce to bolster the flavor profile.

Four cuts of filet mignon from the tenderloin, wrapped in bacon to enhance flavor.

Strip

- This cut is also known by a host of other names, including the New York Strip and Kansas City Strip.

- Sourced from the short loin, the strip is another cut of meat that is low in connective tissue (with the muscle having done little work for the cow), resulting in a tender cut of beef.

- Its fine marbling results in great flavor, generally second only to the ribeye.

- As a bonus, strip steaks can also be used to make richly flavorful roast beef.

A typical strip steak, featuring moderate fat marbling.

T-Bone & Porterhouse

- Both the T-bone and the porterhouse cuts are sourced from the short loin of the cow.

- As you might expect, the T-bone steak is named for the distinctively shaped bone which holds it together. Somewhat confusingly, the porterhouse (whose name comes either from an early-1800s restaurant in New York called the Porter House, or a similarly named hotel in Georgia) also has a T-shaped bone, as both cuts are taken from the same region of the animal. Importantly, however, the two cuts are not the same.

- While both a T-bone and a porterhouse contain a T-shaped bone surrounded by a tenderloin on one side and a strip on the other, the difference between the cuts lies in the quantity of meat in each of these two sections.

- Both T-bones and porterhouses contain a large section of strip steak. Porterhouse steaks are cut from the rear end of the short loin, and thus include a larger section of tenderloin. Conversely, T-bone steaks are cut closer to the front end of the short loin, and contain a smaller section of tenderloin.

- According to the USDA, a T-bone must contain a tenderloin filet with a thickness of at least 0.25 inches, whereas a porterhouse must have a filet that is at least 1.25 inches thick. As a result, many porterhouses can weigh two pounds or more.

- Adding further confusion to this equation, the term “porterhouse” also has different definitions outside of the United States. In Britain and the countries of the Commonwealth, a porterhouse is a UK sirloin steak (that is, a US strip steak) on the bone, without the tenderloin – though some British butchers now offer American-style porterhouses, as well. Meanwhile, in New Zealand and Australia, a Porterhouse refers to a strip steak off the bone.

- Both T-bones and porterhouses contain a large section of strip steak. Porterhouse steaks are cut from the rear end of the short loin, and thus include a larger section of tenderloin. Conversely, T-bone steaks are cut closer to the front end of the short loin, and contain a smaller section of tenderloin.

- In general, both T-bones and porterhouses are both fairly large cuts, and as such are fairly expensive – and best shared among friends!

A T-bone steak, with its namesake bone on display.

Top Sirloin

- The top sirloin cut, meanwhile, is very simply named, as it’s sourced from the upper portion of the cow’s sirloin section (just behind the short loin, and under the hip).

- While other cuts from the sirloin section, such as the flat-bone and round-bone sirloin steaks, feature more bone and tougher muscle, the top sirloin does not, and is more desirable for that reason.

- Additionally, the top sirloin is a fairly affordable cut (the cheapest on average of those we’ve discussed in this article), and given this combination of desirability and affordability, it’s one of the most popular cuts in America today.

- Though top sirloin is less tender, less flavorful, and leaner than the other cuts on this list, it isn’t sorely lacking in any of these categories. For the individual who likes to purchase and enjoy steak fairly regularly, then, top sirloin is a great budget alternative.

A typical cut of top sirloin, served here with butter and an onion ring.

Conclusion

With the information we’ve laid out above, you should now be suitably familiar with the basic characteristics of a quality steak, as well as the unique attributes of our top five cuts. This is only the first part of the process to enjoying a great steak, of course; after deciding what you want, you’ve got to go out and buy your steaks, and then cook them properly. To learn more about these two facets of the experience, consult the latter two parts of this Steak Guide: Part II covers how to buy a steak, and Part III deals with cooking and serving techniques. Bon Appétit!

A sizzling T-bone steak on the grill. Check out Part III of this guide to learn some grilling techniques!

This steak guide was written by Preston Schlueter, incorporating prior writings by J.A. Shapira and Sven Raphael Schneider.

from Gentleman's Gazette https://ift.tt/1XWdf2Z

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment

thanks for your feedback