Indistylemen

What are the Differences among British, American, and Italian Suit Styles?

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

A classic men’s suit is usually said to belong to one of two great tailoring traditions: the British and the Italian. What are the hallmarks of each, how can they be told apart, and where do American suit styles factor into the equation? Read on to discover the differences and details.

Between the British, Italian, and American suit styles, each has its own unique geographic characteristics; in particular, the Italian suit has regional variations with different qualities. Some suits also contain hybrid elements of multiple tailoring traditions. In this article, we’ll take a look at the distinguishing features of these individual styles to help you identify where a suit may have originated.

Wearing a suit evokes discipline, power, self-respect and respect from other people around you.

The English Suit

Western tailoring as we know it today originated in Great Britain, specifically in 19th-century London; thus, the business suit with the most traditional styling is most frequently said to be the English (or British) suit. The earliest stirrings of the contemporary suit began with Beau Brummell‘s influential style. In the early 1800s, Brummell laid the groundwork for the suit by eliminating excess ornamentation and volume in menswear, replacing brocaded silks, frills, powdered wigs, high heels and bright colors with the sober simplicity of a dark blue coat, white shirt, buff vest and fawn trousers with black boots. In so doing, even though he didn’t use the exact same material for his pants and his jacket, he created an emphasis on a close-fitting cut for men, one that emphasized clean lines and simplicity. This would later become the modern suit.

Irena Sedlecka’s sculpture of Beau Brummell on Jermyn Street.

Eventually, the longer tailcoat would evolve into a tailless version in the mid-1800s (in a project commissioned from Henry Poole, who are still producing suits on Savile Row), thus marking the invention of the dinner jacket. This more relaxed style would then see wider use as the “lounge suit,” what we consider a business garment today.

The style of the British suit has been defined by certain features that make it clearly identifiable on sight. Brummell’s original design was based on uniforms he wore as a poleman at Eton College and an officer in the Tenth Royal Hussars. This military influence is still prevalent in the way a British suit accentuates the physique and projects authority. This is owed to the strong structure present in its construction; padded shoulders, heavy canvassing, and waist suppression, all close-fitting and designed to accentuate the body. As such, the British suit looks best on men who are slim. Simultaneously with its goal of enhancing the male form, the British suit is always conservative and understated, consistent with being a product of a culture that prizes following the rules. It never looks gaudy or “over the top.” Thus, the British suit is known for its appropriateness in the workplace–though the most strongly structured can project an authority better suited for the boss than for a lower-level staffer (for example, a pinstriped double-breasted suit).

Colin Firth in Kingsman wearing a classic British suit with padded shoulders

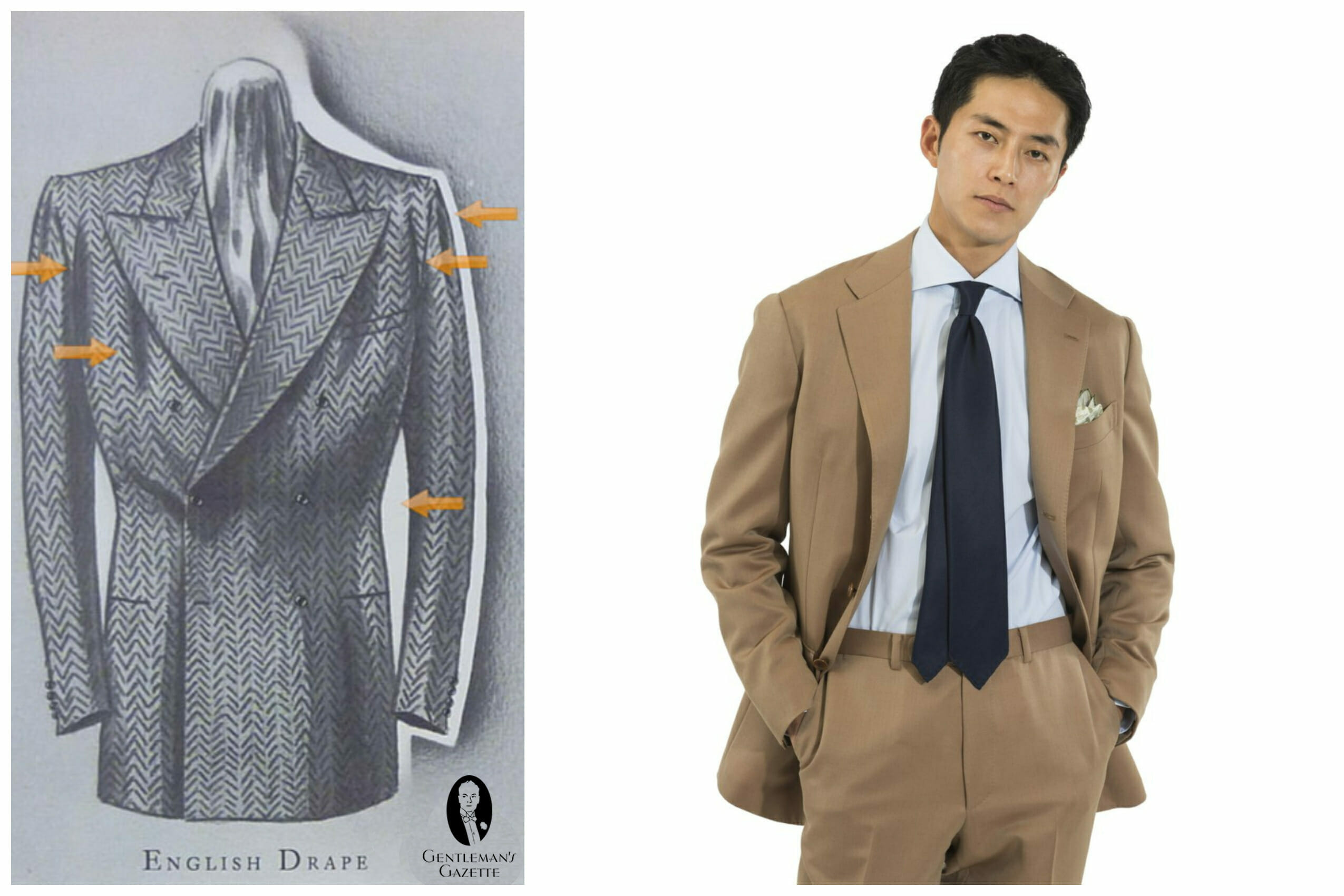

It should be noted that not all British suits are the same. Not only does each tailoring house have its own style, but some suits have taken on Italian or Continental (European) influences, and show hybrid features from these styles. For example, in the 1920s and ’30s, the English drape cut was invented on Savile Row. This involves an added volume of cloth in the chest area–the “drape”–originally with a soft, unpadded shoulder, though it would later evolve into versions with heavy shoulder padding worn by Hollywood actors like Clark Gable and Cary Grant. The drape cut can usually be recognized by the way the chest fabric folds and bunches slightly below the underarms, because of the full chest. This is in some ways the antithesis of the typical slim-fitting British suit, but still has the strong waist suppression to cut an athletic figure, due even more so to the exaggerated chest. It is still made today by a few houses, including Anderson & Sheppard. Although the style has been appropriated elsewhere, if you see the drape cut, you are seeing an originally British concept.

An English drape suit from the 20th century with strong shoulder padding versus a contemporary Japanese Ring Jacket suit with drape to the chest area (and less padding)

A number of features of the British suit are also tied to its equestrian beginnings. After all, Brummell’s Hussars were a cavalry regiment, and gentlemen rode horses until the development of the automobile. These include flap pockets and double rear vents. The vents kept the suit from bunching while on horseback. Flap pockets were similarly designed to keep dirt out of the pockets while in the country, and placing them at a slant was an innovation to facilitate reaching into them while riding. The presence of a ticket pocket above the main side pockets was originally a related mark of the British country suit, as men traveling from London to rural destinations would use the pocket for their train ticket.

A British tweed jacket, featuring angled flap pockets (and a ticket pocket).

Additional hallmarks of English suits are a lower gorge (where the lapel meets the collar, or where the notch is located on a notch lapel) and working sleeve buttons, called “surgeon’s cuffs,” as 19th-century doctors used to operate in suits and would unbutton and roll up their sleeves. Of course, in our global economy, these features are no longer unique to British style; Dutch mega-brand SuitSupply puts working cuffs on its jackets (which are sold globally), and you can get ticket pockets on suits made in Italy for Swedish companies. This is because the template for suits was invented in London and subsequently copied worldwide; however, it’s worth being able to identify which features are British. To call a particular suit British or English in style is therefore most accurate if it contains a combination of traits that originally appeared in England, but perhaps the most defining feature is the overall attention to structure.

The American Suit

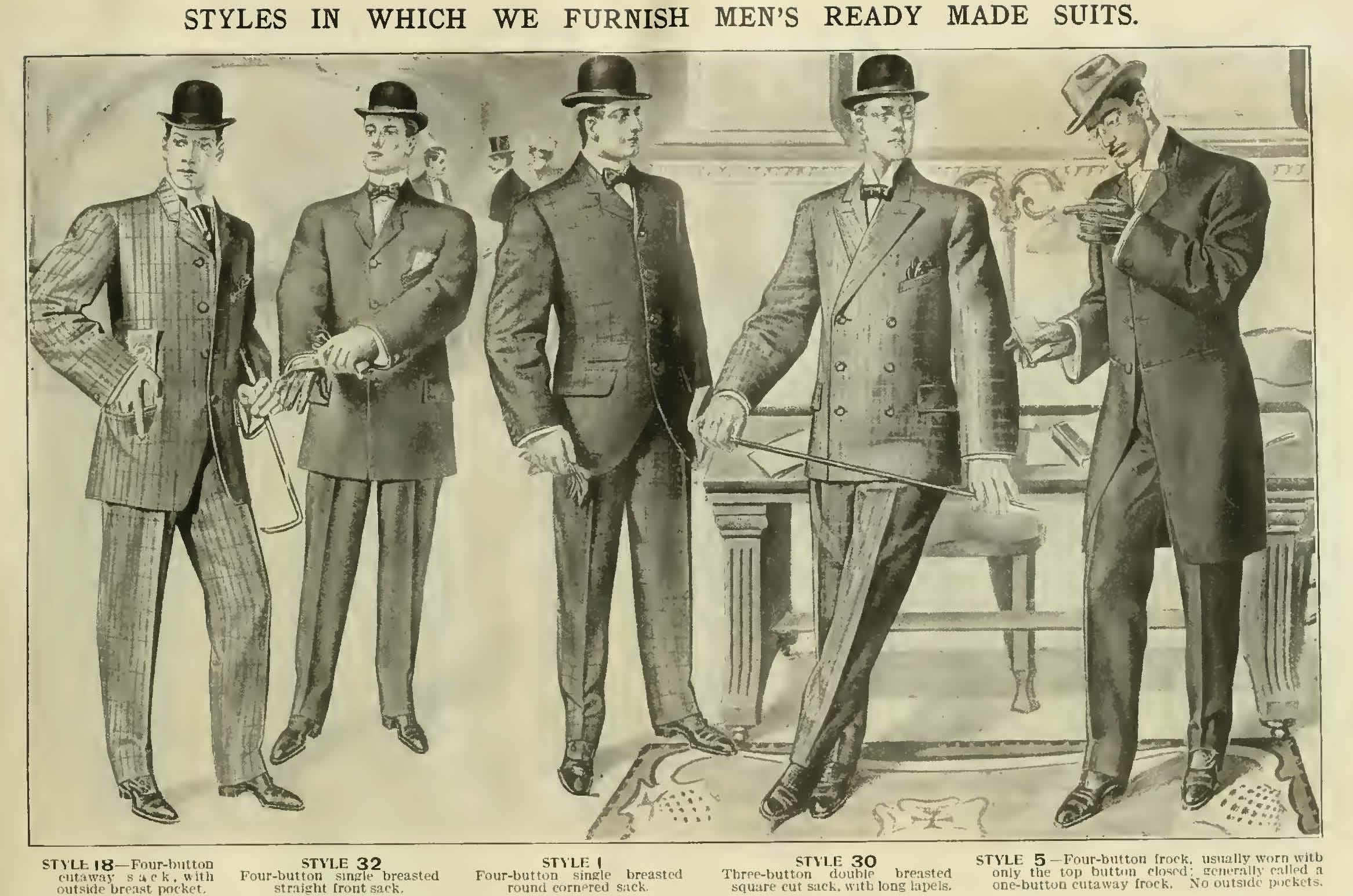

The first major adaptation of British suit style occurred in its former colony, the United States, in the 1920s; this is when Brooks Brothers popularized the so-called “sack suit.” This was a garment with a full, baggy cut made of straight jacket panels, with no interest in contouring to fit the wearer. The accompanying trousers were also wide in the legs. Although the name “sack” was meant to recall the French sacque jacket of the 1840s, which was built on two entirely straight panels, it came to be applied as a negative comment on the way the suit fit like a bag on the wearer. The development of the American sack suit is tied directly to the desire for mass marketing. Brooks Brothers wanted something that was cheap to manufacture (thus its other features of just a single vent and non-functioning three-button sleeves instead of surgeon’s cuffs) and that would fit as many men as possible off the rack. From the consumer’s perspective, the appeal of the sack suit was also its ubiquity. It was, quite frankly, available in stores everywhere, so those who only needed a suit for work or a single event would just pick up what was available. Its low cost also fed its popularity, especially among college youth, for whom it became a key part of Ivy Style. For them, the casual shapelessness of the sack suit had the additional benefit of signaling their rebellion against the “stodgy” formality of their fathers’ suits. Not surprisingly, the sack suit is still quite popular in Japan, where the mystique of Ivy Style continues to shape menswear.

A variety of sack suits, offered in a 1906 Sears catalog.

In its original form, the American suit is the least stylish of the major traditions. It has become associated with poorly dressed politicians in Washington and used-car salesmen on Main Street. With time, though, American suits have been cut slightly closer to the shape of the body. This is owed to the slim-fit trend influenced by Italian style, and to restoring original features of the British suit such as shoulder padding and double vents. However, the loose, shapeless fit of the sack suit still influences most of what can be found at major department stores in the United States. Given that American men tend to have bigger body types than other countries, the impression many have is that the loose fit of the sack suit is best for them. The best approach remains getting suits that are well-fitted to your body, however, so it’s important to try to get an objective sense of how a particular style looks on you. If you are thin or of an average build, the boxy, rectangular cut of the American suit can make you look portly and heavier around the midsection, and if you are a larger man, it can also accentuate your girth if fitted too loosely.

An example of an American sack-style cut from Brooks Brothers.

The Italian Suit

In terms of fit, the Italian suit is essentially the opposite of the American sack as the slimmest fitting of all. It also differs considerably from the British suit. First, it should be noted that “Italian suit” is less of a catch-all term than British suit, since the tailoring tradition of Naples differs markedly from that of Milan. The Neapolitan suit is the most unique, and the distinction begins at the shoulder–which, in contrast to the British style, is unpadded and natural. You can also find elements like spalla camicia (the “shirt shoulder,” lightly pleated where the sleeve joins the armhole) or con rollino, where the sleevehead (top of the sleeve) is attached to the armhole a bit higher than the shoulder, creating a ridge or “roping” detail. Lastly, there may be patch pockets, which speak to the more casual nature of the style when compared to English formality.

Difference Neapolitan vs. American Style

Overall, these differences reveal the greater flamboyance of the Italian style, something that is also reflected in the prevalence of a wider 3-roll-2 lapel, and a curved chest pocket (called barchetta or “little boat”) on the Neapolitan suit. Italian suits from Naples have more open quarters, with the cloth cut in a curved fashion, so you can see the bottom of the front panels sweeping back from the opening (whereas in British tailoring, the quarters of the suit tend to be straighter and more closed). Those who wear the style therefore signal that they don’t take tailoring too seriously, but see it as an expression of individual style. They also need to have a certain panache to carry off the look. For these reasons, the Neapolitan style may not be as safe for work. In essence, the lack of physical structure in the Neapolitan suit–its absence of padding and even canvassing–reflects the more relaxed attitudes and the warmer climate of Southern Italy, as opposed to the stiff upper lip and rainy environment of the British Isles.

English vs. Neapolitan jacket

Because of this cold and rainy climate, British suits feature heavier fabrics and canvassing. If you look at English suit fabrics from the Golden Age of classic style, they tend to be extremely heavy, from 13 ounces and up. Though these are not common today, we can still find thicker material, like tweed, as a characteristic of British jackets and suiting, which speaks to this legacy. Italian suits, as a product of a Mediterranean climate, are considerably lighter as a whole.

Gianni Agnelli in a gray flannel suit from Caraceni.

Though the Italian suit is now often equated with Naples in the #menswear world, the first version to hit the global scene was actually designed by the Roman tailoring house Brioni in the early 1950s. This suit also featured the slimness of fit common to the Italian style as a whole, but was (and is) more conservative than what you’d find in the Neapolitan style. To maintain a fitted profile, the original Italian suit was made with no rear vent, and with jetted (besom) pockets to keep the look clean. Since then, most Italian suits now feature two vents, and while the pocket style matters less, you can perhaps find a greater emphasis on the jetted pockets in suits designed by some Italian tailors with strong connections to Rome, like the Caraceni dynasty. The suits made in Milan also differ in their greater emphasis on a strong, extended shoulder, rather than a natural one–a feature that also appears in Florentine tailoring (for example, in suits made by Liverano & Liverano). The shoulder is not created with much padding, however, so it still has more in common with Neapolitan suits than with the heavy structure of the British make.

The cloth vault at Liverano & Liverano.

Which Suit Style is Best?

This question is perhaps inevitable, but difficult to answer definitively. The best response is to choose that which suits your needs, both physical and situational. If you need something for a conservative office, a British or a more conservative Northern Italian suit may be your best choice, whereas if you want to dress for a night out, you might go Neapolitan. If you are smaller in stature, the high gorge and shorter jackets of Italian suits may create an impression of height, while a thin build can be flattered by their slim cut or built out by the structure of a British version. If you are young and more fashion-forward, a suit made in Naples may appeal to you, but if you are older and more traditional, go British.

An Apparel Arts illustration from 1936, featuring different styles of cut. Can you tell them apart?

Though it is tempting to claim that the loose cut of the American suit is useful for those men who have larger builds, it can equally be said that American suits don’t look best on anyone. It’s always preferable to have a garment that fits closely to your form, no matter what your shape is. To their credit, American suits have become more streamlined in some cases, but this is owed to the popularity of Italian and British versions, fueled by the online menswear movement, and the related need for companies in the United States to compete. Ultimately, we are already beginning to see the signs of an international or global suit style that has taken precedence above all. This marries attributes of the British and Italian tailoring traditions to satisfy the desires of men who are now more educated on the individual features of a well-made suit.

Which suit style do you prefer? Share your views in the comments section.

from Gentleman's Gazette https://ift.tt/2Ij0ywL

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment

thanks for your feedback